Max McGee never would have made it in Roger Goodell's NFL.

Then again, neither would many of his contemporaries.

McGee, who died Saturday after falling from the roof of his home in Minnesota, was a symbol of a league that no longer exists. One in which players went out on Saturday night, caroused to their heart's content, and then showed up on Sunday and played their hearts out.

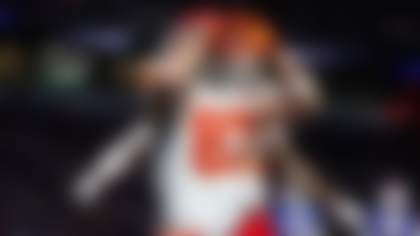

Photos ...

[![internal-link-placeholder-0]](../photo/photo-gallery?chronicleId=09000d5d80376fbb)

From Bobby Layne through Paul Hornung and Joe Namath to dozens of lesser known players like McGee, the routine was liquor, ladies and late hours. Players were rarely fined, no one ever heard of steroids, and no one ever got suspended - except Hornung and Alex Karras, for what was then (and now) the one great sin, gambling.

McGee was the third wide receiver on Vince Lombardi's great Green Bay Packers, who won three NFL titles between 1961-65, then the first two Super Bowls.

He was one of the heroes of the first AFL-NFL championship, as it was then called, a 35-10 win over Kansas City. He caught two touchdown passes from Bart Starr after spending the night "on the town." After a couple of hours of sleep, he showed up in the locker room to discover that Boyd Dowler, the starter, was out with a shoulder injury and he would have to start.

"I was just sitting there, dozing in the sun, and Lombardi yelled 'McGee get the hell in there!' " McGee told Lee Remmel, the team's historian and a local newspaper reporter in those days.

So at age 33, after a season in which he had just four receptions, McGee had a game that made him a part of NFL history. Otherwise, he might have been a footnote, although he did have a productive 12-season career: 345 receptions with an 18.2-yard average per catch and 50 touchdowns.

McGee's day received notice because it was in that first Super Bowl. Otherwise, no one would have raised an eyebrow - certainly not in the commissioner's office where there was no personal player conduct policy like the one instituted by Goodell after he took office last year following a rash of run-ins by players with the law.

Had there been, who knows how many players would have been brought before Pete Rozelle?

But the attitude back them was "boys will be boys," both within the NFL and within society.

Players from that era talk with a slight chuckle about teammates being pulled over for DUI, showing their licenses and having the police involved suddenly change their outlook in the presence of celebrity. The next thing they knew, one police officer was driving them home and another was driving the player's car to safety.

Rarely was anyone charged and most often nothing was ever made public.

"Everyone accepted it," says Gene Upshaw, the executive director of the NFL Players Association. "It was just part of the way society was in those days."

Upshaw played from 1968-82 for the Oakland Raiders, who have always been a landing spot for players who had trouble fitting in elsewhere. John Matuszak was the poster boy for that, the first pick by Houston in the 1973 draft whose off-field behavior soon landed him in Kansas City and eventually with the Raiders.

"A lot of guys prided themselves on our reputation," Upshaw recalls. "It was like we had an advantage just walking on the field. The other guys would back off. It was like 'Here come the bad boys.' "

McGee had that reputation and so did Hornung and some of their other teammates.

Still, when McGee caught those two TD passes in the Super Bowl after his night on the town, it was part of the culture.

Copyright 2007 by The Associated Press