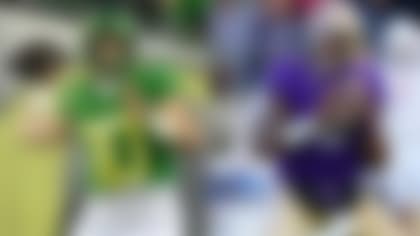

Which cornerback is the most dangerous defender: Marcus Roberson or Loucheiz Purifoy?

That's the dilemma SEC quarterbacks will face on a weekly basis when deciding which of the Florida Gators' ultra-talented cornerbacks should be targeted in the passing game.

Whereas most teams might have one corner capable of blanketing an elite receiver on the edge, the Gators have two of the best cover corners in college football. Each specializes in mauling receivers with a tenacious and aggressive style, while also demonstrating the athleticism, awareness and ball skills to make plays in man or zone coverage.

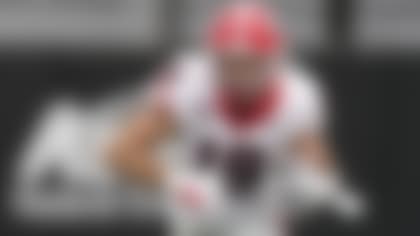

Purifoy is a freakishly talented athlete with the speed, quickness and movement skills defensive coaches covet in a No. 1 corner. The 6-foot-1, 195-pound junior is a natural press corner with the length and range to mug receivers at the line. Although his technique is far from polished, his combination of athleticism, agility and physicality makes it tough for elite receivers to earn separation down the field, particularly when he uses his hands to jam and disrupt early in the route.

As a run defender, Purifoy is an aggressive hitter with a strong nose for the ball. He isn't afraid to step up to meet runners on the corner, which allows him to set the edge for the defense when playing cloud coverage. Additionally, Purifoy's combination of aggressiveness and physicality makes him a dangerous rusher off the edge on "cat" blitzes.

The Gators have also tapped into Purifoy's athleticism and versatility by using him on offense and special teams. He spent most of the spring working at wide receiver after playing a minimal role on offense a season ago (one reception for five yards; one rush for eight yards). In the kicking game, he is one of the most dangerous playmakers on the field with a knack for blocking kicks (a blocked field goal and punt in 2012), delivering big hits and solid kick returns.

Given his immense talent, athleticism and versatility, it is not surprising NFL scouts are already salivating about his potential at the next level.

Roberson, a 6-foot, 195-pound junior, is a polished technician with exceptional quickness and movement skills. He is adept at shadowing receivers from "off" coverage utilizing bail technique, but also shows solid bump-and-run skills at the line. Additionally, he displays natural instincts, awareness and ball skills in coverage. Roberson finished second in the SEC among returning players in passes defended with 14; his 12 pass breakups were the most since Joe Haden recorded 12 in 2008.

Although he is not a big hitter or consistent tackler at this point in his career, Roberson finished with 23 tackles in 2012 and shows a willingness to throw his body around that is encouraging. If he can improve in this area, he could develop into one of the most complete corners in college football.

The University of Florida is always a "must-visit" destination for NFL scouts based on the impressive collection of talent routinely assembled on both sides of the ball. But this fall, evaluators will spend most of their time checking out a pair of cover corners with the potential to become game changers at the next level.

The evaluation of cornerback is becoming more difficult with more college teams designating a "boundary corner" and "field corner" in their schemes. NFL coaches and scouts are being challenged to abandon their conventional thoughts when looking at college corners on tape. In previous years, college coaches would routinely place their top corner to field because the No.1 cover man possesses the speed, quickness and instincts to cover a wider area without help from the safety. Teams would lock the field corner in man coverage or some variation of man-to-man and roll the safety over the top of the weak-side or "boundary" corner to provide him with additional help. With most teams lacking two quality cover guys on the outside, this strategy would allow teams to protect an inferior cornerback in coverage.

This tactic, however, is changing across the college landscape with more teams assigning their No.1 cornerback to play the boundary position. The proliferation of the spread offense has resulted in more offenses using three- and four-receiver sets, with many featuring a variety of 3x1 formations with the No.1 receiver on the backside. Due to the challenge of matching up with three receivers on the strong side, the offense is able to create one-on-one situations with their top receiver on the backside. To counter these tactics, some college teams are placing their top guy into the boundary and rolling the coverage to the field side. Additionally, teams are also placing their most physical cornerback into the boundary to bolster the run defense, while also giving the defensive coordinator the flexibility to use some cornerback blitzes.

When I talked to an NFC Scout about the changing landscape regarding the deployment of top cornerbacks, he told me that he has to spend more time asking defensive coaches why they align their cornerbacks to the boundary or the field. He went on to tell me that evaluators must develop a "better understanding of schemes" to truly assess a prospect's potential as a future starter. An AFC Scout talked at length about how the "boundary" corner designation partially clouded his evaluation on players like Xavier Rhodes and Dee Millner because they spent a ton of time playing into the short side of the field.

With the pro game played primarily in the middle of the field due to the placement of the NFL hash marks, scouts must be able to determine if a top corner can play effectively in space without assistance from a safety. As more college teams tuck away their top corner into the boundary, that evaluation will be a tricky one going forward.

Follow Bucky Brooks on Twitter @BuckyBrooks.